how not to work

2022

In this project my friend Aneeqa and I started to dissect the concept of work. Through self-experiments, hosted conversations and research we explored the origins of our belief in productivity. This project was made within the Invisible studio led by Mario Marinale. The studio evolves around the topics systems thinking, permaculture and deep ecology.

Since our teachers encourage hands-on research I started this project by going to school and not working for 2 hours. But this did feel like work and it made me think: what actually is work?

Hypothesis 1: We need a new definition of work.

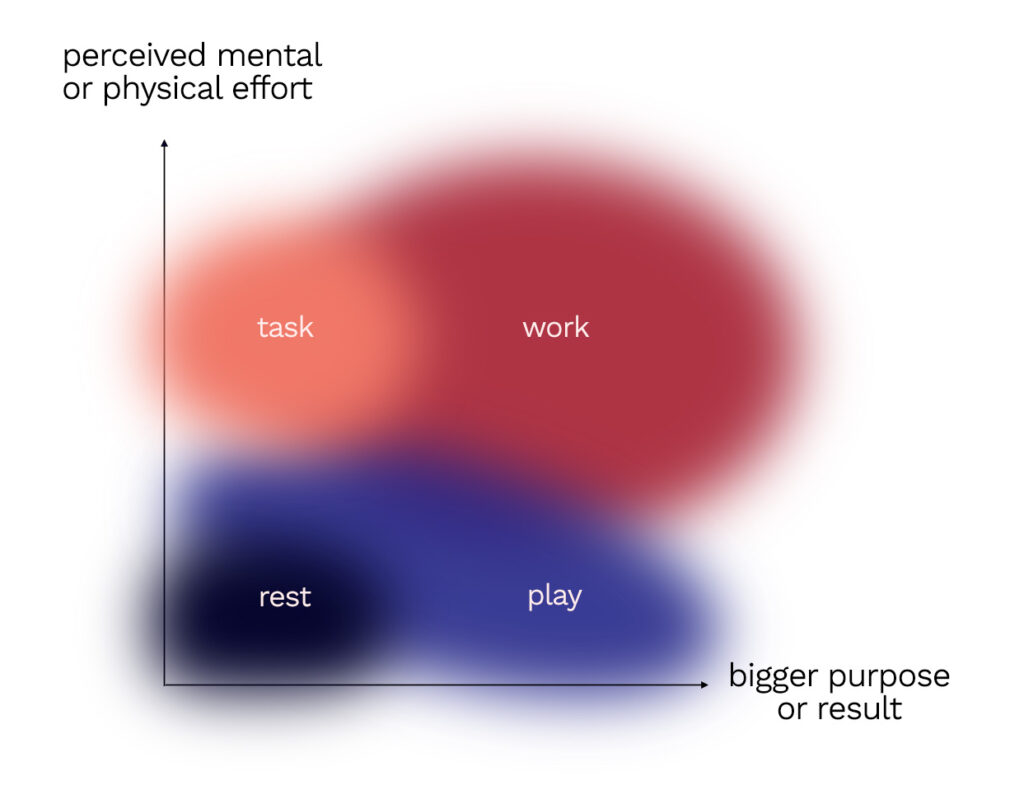

Oxford languages defines work as “activity involving mental or physical effort done in order to achieve a purpose or result.” Since this can apply to almost everything (like going downstairs to the fridge (physical effort) to get ice cream (purpose)) we developed this definition a little further.

work = activity involving perceived mental or physical effort while doing the activity to archieve a purpose or result that is bigger than the activity itself

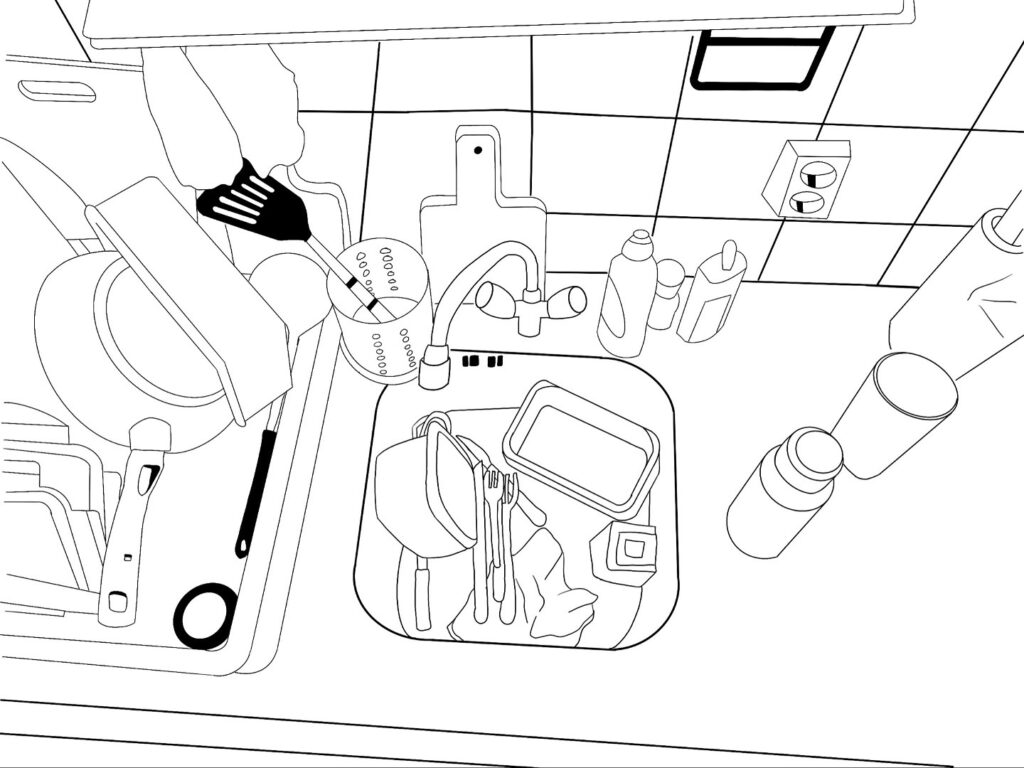

Since most of our activities have some purpose or result, in our definition work is something that has a purpose beyond completing the activity. If you wash dishes to have clean dishes in our definition this would be a task, not work. In contrast if someone pays you to wash dishes or if you aim to impress your parents-in-law by your dishwashing abilities, dishwashing has a bigger purpose than having clean dishes and it becomes work. If you actually enjoy dishwashing and you don’t think it requires much effort, dishwashing might be play or even rest for you.

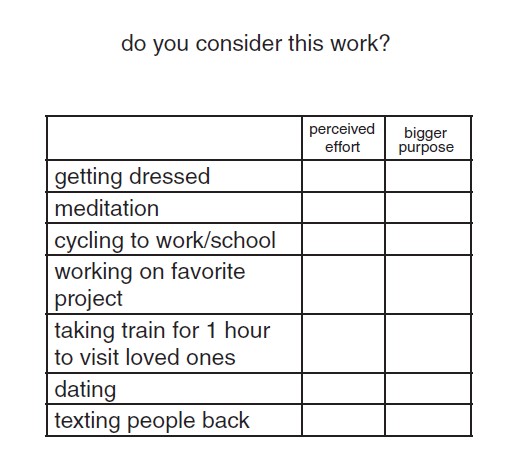

Based on this definition we came up with this diffuse four field matrix:

With this situational and highly subjective definition of work at hand we went through different activities and checked if they classify as work. This resulted in some surprising findings (visiting my grandma and texting people back is work for me).

Hypothesis 2: Our current digital age turned a lot of leisure activities into work.

While videos on how to live a better life partly promote rest and leisure activities, these are often performed to be able to work better (”how to rest to be more productive”) not for its own sake and out of pure enjoyment.

Reading sounds like a leisure activity but if we read 15 pages every morning to become a more successful, focused person, the act of reading becomes work. When we aspire to become great at baking to start a successful blog, baking is work. When we meditate, because we want to be more focused and productive, meditating becomes work.

Hypothesis 3: We still think that work is inherently good and laziness is bad.

Although we live in a rather atheist society past religious beliefs (”laziness is a deadly sin”) seem to subconciously continue. Current internet culture highly promotes the idea of living a productive life. When we hosted tea picnics in our school hallway we realised how we all feel bad when we’re not working, when we’re being “lazy”.

and yes, sometimes you think ok I need to rest, but how do I do it? Where do I even start? Cause as soon as you maybe start doing something, it becomes work.

I feel like there’s no rest in my body most of the time. And I feel useless when I’m not doing anything. So, I feel guilty when I relax or watch Netflix or something. So I’m just always working. Also, I just go to bed whenever I’m tired. I just keep on working and then when my eyes start closing usually around one, and then I instantly sleep because I’m really tired.

I want to imagine a whole forest of useless trees, branches densely interwoven, providing an impenetrable habitat for birds, snakes, lizards, squirrels, insects, fungi, and lichen. And eventually, through this generous, shaded, and useless environment might come a weary traveler from the land of usefulness, a carpenter who has laid down his tools. Maybe after a bit of dazed wandering, he might take a cue from the animals and have a seat beneath an oak tree. Maybe, for the first time ever, he’d take a nap.

How to do Nothing by Jenny Odell

In a world where no one is compelled to work more than four hours a day every person possessed of scientific curiosity will be able to indulge it, and every painter will be able to paint without starving, however excellent his pictures may be.

In Praise of Idleness by Betrand Russell, 1932